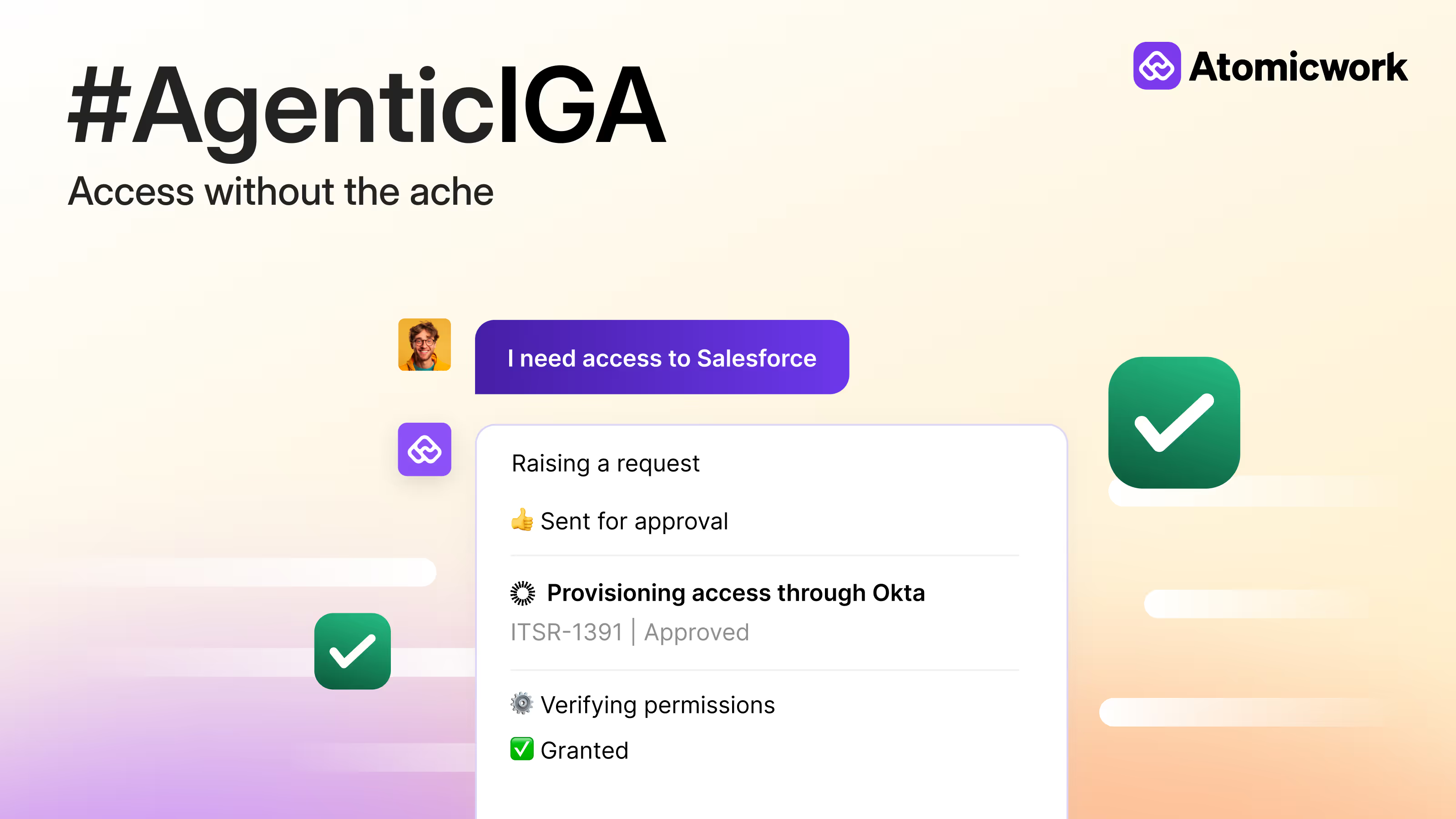

Rewiring the fundamentals of access provisioning with agentic AI

When people talk about Identity Governance, the conversation usually starts with audits, reviews, and compliance.

When I talk to peers — PMs, IT leaders, security teams — the frustration usually shows up somewhere else entirely: access provisioning.

That gap is what stood out to me most while working on Agentic IGA!

Access provisioning isn’t just an operational detail. It’s the point where identity governance either works in the real world, or quietly breaks down under day-to-day pressure.

I look back at my conversation on a podcast roundtable with my colleagues and engineers of Atomicwork, on what it really took to build IGA but also the why behind it all. Read on.

Why we started with access provisioning

One of the first things that surprised me was how much access provisioning dominates IT work. Across customers and internal data, we consistently saw that 30–40% of IT requests were access-related.

Not because organizations lack governance, but because access sits right at the intersection of identity, policy, and real work.

That’s why, when we started building IGA at Atomicwork, we didn’t begin with access reviews or reporting. We started with access provisioning because that’s where governance is tested continuously, not quarterly.

What makes access provisioning deceptively hard

From the outside, access provisioning looks transactional but in practice, almost every request arrives underspecified.

What’s presented as a single request often hides multiple unresolved decisions like the:

- Scope of access

- Appropriate entitlement

- Duration

- Applicable policy

As Anish put it during our internal discussions:

“The data itself is fragmented in multiple places — different IDPs, different apps, and sometimes apps that aren’t even part of the IDP and still need to be manually provisioned.”

That fragmentation forces humans to step in. Administrators aren’t just executing requests — they’re resolving ambiguity the system can’t.

Where traditional access management struggled

Most IGA systems assume access requests arrive fully formed and that rules can cleanly map people to permissions.

That assumption breaks down fast.

As Anish explained it to me early on in the conversation:

“An IT admin is actually going in and giving access to each individual app based on role and job title.”

Not because IT teams lack discipline, but because access decisions require interpretation. Rules work best in static environments. Access provisioning lives in environments that change constantly.

What we learned from our first implementation

Our initial approach followed a familiar pattern: detect intent, create a request, run a workflow.

Technically, it worked. Practically, it felt wrong.

As I shared in our roundtable: earlier, someone would ask, we’d create a request, and the workflow would kick in but it wasn’t a two-way conversation.

That was the turning point for me as a PM.

Access provisioning isn’t a one-step transaction. Users often don’t know exactly what they need. The system needs to clarify intent before it can act responsibly.

Workflows execute steps. They don’t reason.

The shift to agentic access provisioning

The biggest change we made was architectural.

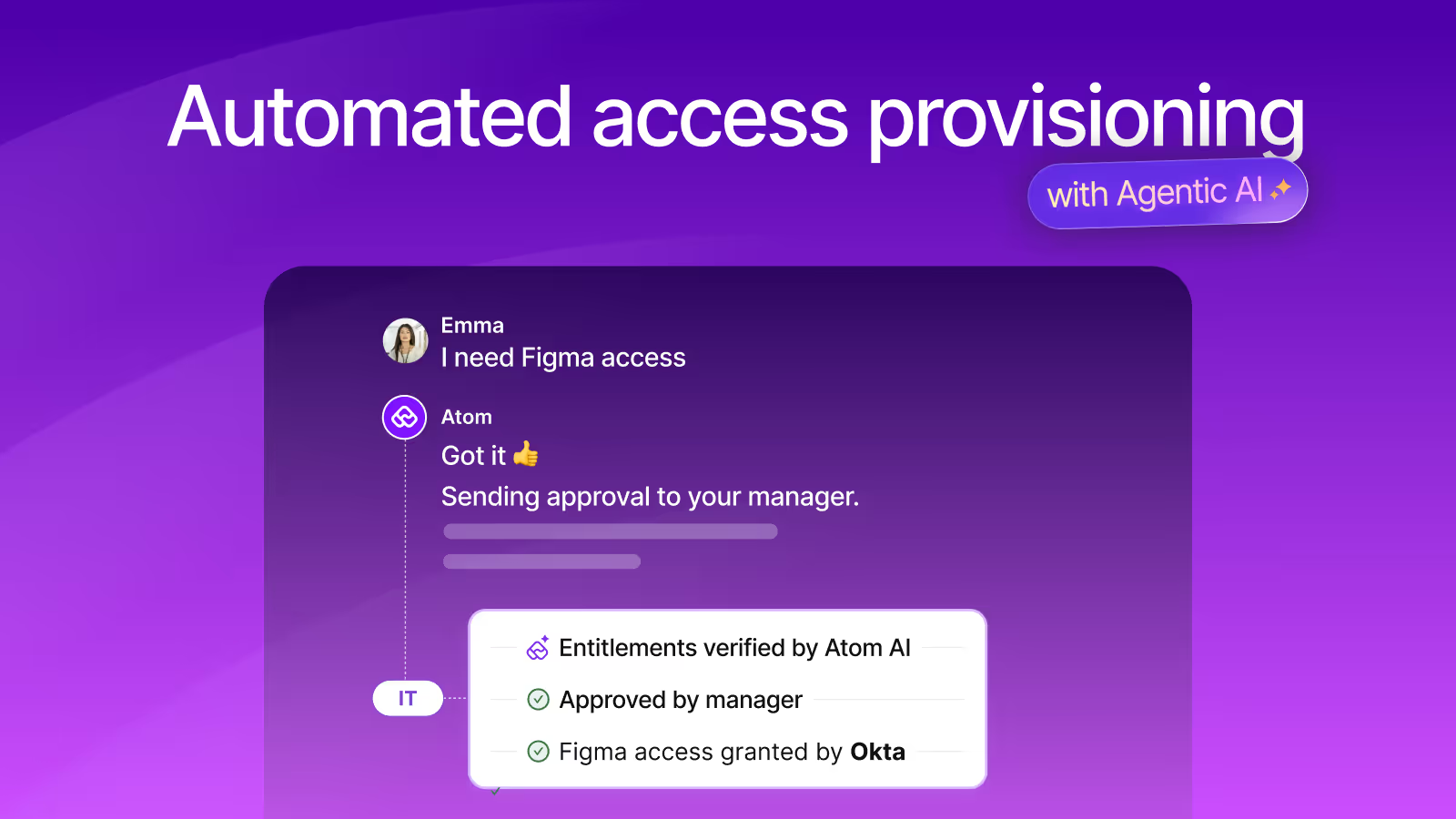

Instead of treating access requests as inputs to workflows, we introduced a specialized Identity Governance agent within Atom’s multi-agent framework.

When Atom detects an access-related request, it hands the interaction to this IG agent. That agent has access to search, policy evaluation, approval logic, and existing entitlement data and can reason across them before provisioning anything.

Arkajit summarized this shift well:

“Atom can hand off to a specialized agent that has access to search, policy, and entitlement tools, to figure out what exactly the user needs.”

What changed wasn’t just automation, it was where governance happens.

Governance moved from after-the-fact enforcement to in-the-moment decision-making.

Why intent mattered more than rules

One of the hardest problems we had to solve was ambiguity.

As Shamith pointed out during the discussion:

“It’s not just about a lookup, it’s about collating policies and understanding what the user is entitled to.”

A single request can map to very different outcomes depending on context. Keyword-based systems tend to over-permission by default. That risk only shows up later, during audits or reviews.

By combining semantic understanding, entitlement metadata, and policy context, the IG agent reasons from what the user is trying to do to what access is appropriate — while staying inside governance boundaries.

Why we leaned into granularity

Another lesson that shaped the system was how much tool granularity matters.

Instead of giving the agent a single “grant access” capability, we exposed granular tools like checking existing access, evaluating approval requirements, enforcing time limits, granting or revoking entitlements.

As Arkajit explains:

“Granular tools give the agent room to reason without blindly taking action.”

That distinction matters because identity governance isn’t about speed alone. It’s about making decisions that can be explained, audited, and reversed.

Provisioning and de-provisioning are the same problem

One thing that became obvious very quickly: treating de-provisioning as a separate cleanup step doesn’t work.

Access often needs to be time-bound. Roles change. Projects end. If removal depends on manual follow-up, it will be missed.

So the agent gathers duration conversationally, enforces policy limits, and automatically de-provisions access when that time expires.

Provisioning and de-provisioning become part of the same governed decision, not two disconnected processes.

What this launch represents to me

Our IGA launch wasn’t about making access provisioning faster.

It was about making it defensible, contextual, and trustworthy, with AI agents that reason within governance instead of bypassing it.

The belief that shaped everything we built is simple: If identity governance can’t handle access provisioning well, it can’t really govern identity at all!

If we do this right, access provisioning won’t disappear because it was automated.

It will disappear because it no longer feels like a problem worth talking about.

That’s the bar we’re setting with Agentic IGA. If this problem resonates with you, I’d love for you to give it a try and share your feedback.

You may also like...